The contention that alcohol causes weight loss is controversial. For while there is an association between alcohol intake and body weight, it is problematic trying to ascribe cause and effect in this relationship. In addition confounding variables interfere with the relationship and further muddy the picture. However, that being said, evidence in the literature does suggest that alcohol causes weight loss because the ethanol component of alcoholic drinks may alter metabolic flux to increase resting metabolic rate (RMR). Ethanol contains 7.1 kcal per gram which is more than both carbohydrate and fat, and yet when ethanol is consumed along with a mixed diet, weight loss occurs1. It is suggested that the activation of wasteful metabolising pathways such as the microsomal ethanol oxidising system (MEOS) located in the hepatic endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for this effect. Further, such a system may upregulate with long term regular ethanol consumption. In addition, oxidation of ethanol in this way is not linked to the conservation of energy, as might be expected from other oxidation pathways.

The contention that alcohol causes weight loss is controversial. For while there is an association between alcohol intake and body weight, it is problematic trying to ascribe cause and effect in this relationship. In addition confounding variables interfere with the relationship and further muddy the picture. However, that being said, evidence in the literature does suggest that alcohol causes weight loss because the ethanol component of alcoholic drinks may alter metabolic flux to increase resting metabolic rate (RMR). Ethanol contains 7.1 kcal per gram which is more than both carbohydrate and fat, and yet when ethanol is consumed along with a mixed diet, weight loss occurs1. It is suggested that the activation of wasteful metabolising pathways such as the microsomal ethanol oxidising system (MEOS) located in the hepatic endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for this effect. Further, such a system may upregulate with long term regular ethanol consumption. In addition, oxidation of ethanol in this way is not linked to the conservation of energy, as might be expected from other oxidation pathways.

Researchers have investigated the association between energy expenditure and alcohol consumption and reported that alcoholics have higher resting metabolic rates compared to non-alcoholics. For example in a study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition2, researchers measured the resting energy expenditure of alcoholics with fatty liver disease, alcoholics without fatty liver disease and normal healthy subjects using indirect calorimetry. The results showed that alcoholics without fatty liver disease had significantly higher resting energy expenditures compared to normal healthy subjects and alcoholics with fatty liver disease. The VO2 and VCO2 was also significantly higher in the alcoholics with normal livers, compared to the other two groups. However, when the authors used the traditional Harris-Benedict equation (body mass index multiplied by a factor to take into account physical activity) they found no difference between the groups, suggesting that traditional textbook measures of energy expenditure are not accurate regarding alcohol metabolism.

In this study the authors were careful to measure resting metabolic rate two hours postprandially rather than in the fasting state, in order to nullify the effects of the activating energy required for the gluconeogenic and ketogenic pathways. This allowed the authors to state more definitively that alcoholics have higher resting metabolic rates compared to non-alcoholics, and fatty liver disease attenuates this association. This supports the hypothesis that the hepatic endoplasmic reticulum MEOS might be responsible for the increased energy in those who consume alcohol regularly, because liver damage may reduce this effect somewhat. Upregulation of MEOS has been reported mostly in animal experiments, but human studies confirm that the effects are real and relevant to human subjects. Because around 25 % of the resting energy expenditure of humans is accounted for by the metabolic function of the liver, it is not unreasonable to assume that a small increase in MEOS flux could have a considerable effect on the total energy expenditure and oxygen consumption of the body.

The advice to avoid alcohol in those wishing to lose weight is based on the ‘eat-too-much, do-too-little’ energy balance theory of weight gain. This theory assumes that ethanol provides its 7.1 kcal per gram of energy and that if this is not burnt up through exercise, it will be stored as fat. However, this calorie counting obsession that pervades the mainstream medical establishment is erroneous because it assumes that calories are used efficiently in humans. That ethanol and other dietary factors might be metabolised inefficiently is never considered. The calorie is a calorie brigade do not fully understand, or conveniently forget to suit their agenda, that human metabolism is far more complicated than subtracting the energy used in physical activity from the energy ingested in food. The presence of MEOS is a fascinating prospect because not only does it demolish the textbook energy balance fallacy, it also invites speculation as to how nutrition might affect the MEOS systems. If alcohol causes weight loss through activation of MEOS, dietary intake may further modify this effect.

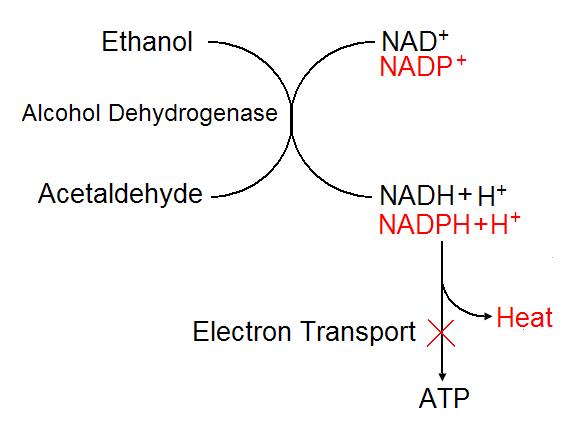

Biochemically, MEOS seems to involve a loss of energy and there appears to be no coupling of the pathway to the production of ATP. This may be because unlike normal oxidation of ethanol in the mitochondria, MEOS in the endoplasmic reticulum produces NADPH (rather than NADH) which is not available for electron transport and energy production. As a result MEOS dissipates the energy produced from the oxidation of ethanol as heat (figure 1)4. Animal studies have shown that MEOS might not be limited to hepatocytes, but also be involved in the metabolism of drugs in adipocytes. Human studies show that increasing ethanol consumption to 2000 kcal per day only increases weight gain by 6 grams per day, but similar increases in chocolate intake cause weight gain of 198 grams per day4. In this case the extra weight is unlikely to be explained by diuresis because chronic alcohol intake causes net fluid retention. Examination of fecal matter also shows that the extra weight is not accounted for by excretion. Therefore the potential that alcohol causes weight loss is real and supported by evidence.

![]()

Figure 1. Potentially, alcohol causes weight loss because the microsomal ethanol oxidising system allows the inefficient use of ethanol to produce heat, rather than ATP. In the microsome, the NADP molecule (red) replaces the NAD molecule (black) found in the mitochondria. This causes the energy derived from oxidation to be dissipated as heat rather than producing ATP through mitochondrial transport.

Figure 1. Potentially, alcohol causes weight loss because the microsomal ethanol oxidising system allows the inefficient use of ethanol to produce heat, rather than ATP. In the microsome, the NADP molecule (red) replaces the NAD molecule (black) found in the mitochondria. This causes the energy derived from oxidation to be dissipated as heat rather than producing ATP through mitochondrial transport.

RdB