Fibre has traditionally been seen as a non-caloric nutritional substance that aided the passage of food through the gut. However, more recently the specialist nutritional literature has changed this viewpoint, and fibre is now considered far more diverse and important that it once was. For example, the concept that fibre supplies no energy has been proved to be false. Research now shows that the fermentation of mainly cellulose fibre to short chain fatty acids by gut bacteria, and their subsequent absorption and utilisation for energy production, is a significant contributor to the total energy needs of man. These short chain fatty acids may also favourably modulate plasma lipoproteins by inhibiting hepatic cholesterol synthesis. In addition, the unique role of soluble fibre at slowing the absorption of glucose in the intestine has been shown to be necessary in the prevention of Western diseases. A number of Western diseases including cancer and cardiovascular disease are now thought to have associations with low intake of dietary fibre.

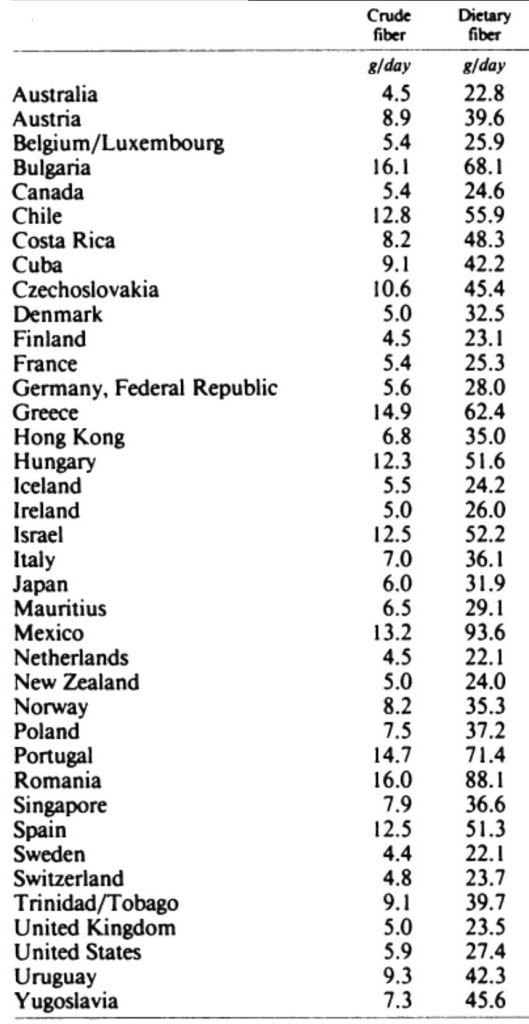

Estimates of the per capita intakes of fibre have been made and they make for interesting reading. For example in one study1, the fibre intakes of various countries were assessed using data collected from questionnaires on food intakes. Fibre sources included total cereals, wheat, rice, corn, other cereals, roots, tubers, legumes, vegetables, and fruits. The main source of fibre in all countries was cereals, and total estimates of cereal fibre matched previous estimates based on other data gathering methods. The range of fibre in the diet was wide, with Australia being the lowest at 22.8 grams per day, while Mexico was the highest at 93.6 grams per day. The fibre intakes of the various countries can be seen in figure 1. As can be seen the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and other Westernised countries in North America and Europe had low intake of dietary fibre. In contrast developing nations and those in Eastern Europe had higher intakes. These values likely reflected the degree to which the country in question has adopted the typical Western diet.

A shift from mainly plant sources of protein to animal sources that occurs in the Western diet is responsible for this lowering of the dietary fibre intake. In addition, the refining of grains also contributes significantly to this effect, as is common in Western foods. Differences in the sorts of food can also be an important determinant of total dietary fibre intake, For example, in Belgium, Finland, Iceland and the Netherlands, roots and tubers were a major source of fibre, but tubers did not contribute significantly to fibre intake elsewhere. Vegetables contributed 25 % of fibre intake in France, Italy and New Zealand. Fruit was a significant contributor of total dietary fibre intake in Trinidad and Tobago at 29.6 % of the total intake, but in Romania only contributed 3.1 %. Only Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore ate significant quantities of soybeans. Legumes contributes no more than 14.9 % of total dietary fibre in any country. Legume fibre has consistently been shown to be highly beneficial to health and had less developed countries been included, this figure would likely have been far higher.

RdB