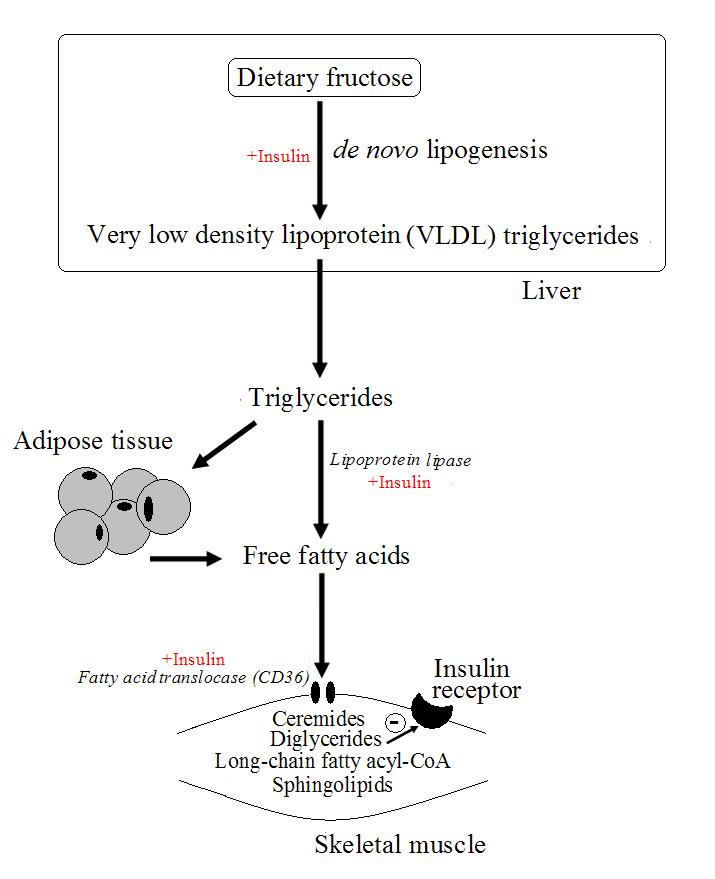

The development of metabolic syndrome, characterised by insulin resistance, abdominal obesity and blood lipid changes, is a risk factor for a number of serious diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity. Insulin resistance is a complex phenomenon and is not fully understood but is theorised to be caused by ectopic fat accumulation, particularly in the liver and skeletal muscle. The increased supply of triglycerides and free fatty acids that causes non-adipose fat accumulation, may be the result of high fructose diets, which are known to increase de novo lipogenesis in the liver, as has been demonstrated in humans studies and animal models. The fat accumulation in skeletal muscle may decrease the ability of the tissue to oxidise fatty acids and therefore allow accumulation of lipids metabolites in the form of diglycerides, long chain fatty acyl-CoA, ceremides and sphingolipids that may interfere with the insulin signalling pathway (figure 1).

Figure 1. Possible mechanism leading to insulin resistance based on high intakes of dietary fructose.

Dietary intervention to treat obesity caused by the metabolic syndrome has traditionally centred around creating a negative energy balance by forced exercise in combination with calorie restriction. However the long-term failure rate of such diets is extremely high, and this is likely due to the underlying metabolic dysfunction that remains despite apparent weight loss. Without treatment of the underlying insulin resistance through reversal of the fatty acid accumulation in the skeletal muscle, exercise cannot be effective long-term because the skeletal muscle has an impaired ability to oxidise fatty acids. In addition, insulin resistance decreases glycogen stores, thus further lowering the work output of muscle. Reducing calorie intake, often without any consideration of the quality of the diet, ensures that the supply of fatty acids and lipids to muscle and liver maintain insulin resistance. A strategy to decrease the underlying metabolic dysfunction is therefore necessary to treat obesity.

Dietary interventions to improve insulin sensitivity have been investigated, and a number have proved successful. In particular, the use of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFAs) may be beneficial. For example, researchers1 have used a single-blind cross-over study to investigate the effects of 3 types of high fat meal on the insulin sensitivity of 10 insulin resistant men. The fat meals were either high in saturated fatty acids (SFAs) (palmitate), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) (olive oil) or high in PUFAs (safflower oil and fish oil). Fatty acid uptake, as measured by assessing arteriovenous fatty acid concentrations across the forearm muscle, was lower for the PUFA meal compared to the other treatments. In addition, the SFA meal caused significant increases in plasma insulin and glucose compared to the PUFA meal, with the MUFA meal having an intermediate effect. The PUFA meal also induced less down-regulation of the pathways involved in fatty acid oxidation.

These results suggest that the PUFAs in safflower oil and fish oil decrease fatty acid up-take to skeletal muscle, which may have beneficial effects on insulin resistance. Fish oil is a rich source of eicosapentanoic acid (EPA, C20:5 (n-3)) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA, C22:6 (n-3)), and safflower is a rich source of γ-linolenic acid (GLA, C18:3 (n-6)). Plasma triglycerides were unchanged between treatments suggesting that reduced circulating levels of lipid were not responsible for the reduced uptake to muscle. Instead the lower insulin levels may have decreased lipoprotein lipase activity, reducing fatty acid uptake. In addition the fatty acid transfer protein CD36 (fatty acid translocase) is unregulated by insulin, and the lower insulin levels seen with PUFAs may have further decreased fatty acid uptake. PUFAs may therefore decrease fatty acid uptake to skeletal muscle by reducing postprandial insulin levels, with subsequent improvements in insulin resistance.

RdB