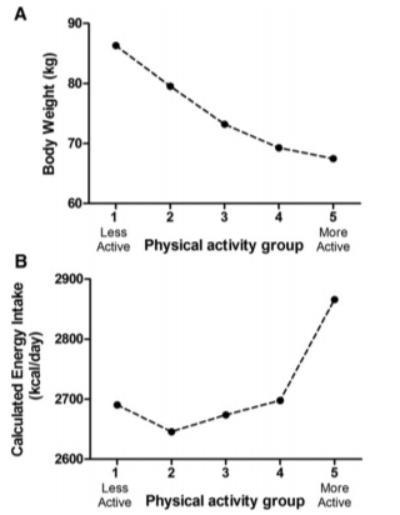

Obesity is characterised by energy dysfunction, and a number of studies have shown that there is an association between energy dysfunction and the amount of physical activity performed. For example, in one study, researchers investigated the relationship between energy intake, appetite, weight gain and physical activity in subjects between 20 and 35 kg/m2 (roughly normal weight to obese). The body composition of the subjects was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and the activity levels of the subjects were measured using an armband that recorded movement. The measurements were repeated every 3 month for 1 year duration. At baseline an inverse relationship existed between body weight and activity levels. Those with the lowest levels of activity (around 15.7 min of moderate to vigorous activity per day) had the greatest body weights whilst those with the highest levels of physical activity (around 174.5 min moderate to vigorous activity) had the lowest body weights (figure 1a).

Obesity is characterised by energy dysfunction, and a number of studies have shown that there is an association between energy dysfunction and the amount of physical activity performed. For example, in one study, researchers investigated the relationship between energy intake, appetite, weight gain and physical activity in subjects between 20 and 35 kg/m2 (roughly normal weight to obese). The body composition of the subjects was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and the activity levels of the subjects were measured using an armband that recorded movement. The measurements were repeated every 3 month for 1 year duration. At baseline an inverse relationship existed between body weight and activity levels. Those with the lowest levels of activity (around 15.7 min of moderate to vigorous activity per day) had the greatest body weights whilst those with the highest levels of physical activity (around 174.5 min moderate to vigorous activity) had the lowest body weights (figure 1a).

Figure 1. Figure 1a shows that as physical activity increases, body weight decreases. However, it is not possible to state the cause and effect. Figure 1b shows that as physical activity increases, energy intake increases. However, for those with the lowest levels of physical activity, who are also those with the greatest body weights, the energy intake is higher that should be predicted from the rest of the data. Both of these sets of data suggest taken together support the contention that obesity is characterised by energy and appetite dysfunction. (see Shook et al, 2015)

The activity data shows that there is an association between body weight and levels of physical activity. However, it does not indicate which of these factors in the cause of the relationship. While the mainstream continues to interpret data such as this as low levels of physical activity being the cause of weight gain, there is good evidence that the opposite is true. The metabolic syndrome, a condition that increases the risk of weight gain and obesity is characterised by an energy storage and utilisation dysfunction. In this regard, hormonal homeostatic mechanisms go awry and this leads to an inability to properly store and utilise energy. As a result the performance of physical activity becomes more difficult because the energy available for such activity becomes limited, due to a metabolic dysfunction that is akin to starvation. In response to this metabolic shortage of ‘available’ energy, the hypothalamus of the brain down regulates physical activity levels and metabolic rate.

Further, the researchers also showed highest intakes occurring in those subjects who performed the most physical activity (2190 kcal/d) and the lowest intakes occurring in those subjects who performed the least physical activity (2004 kcal/d), although the association was not linear (figure 1). This graph is interesting because it also supports the contention that the obese have a dysfunction in appetite regulation. As physical activity increases, the amount of energy consumed also increases. However, those with the least physical activity, which included those with the greatest body weights, show a greater consumption of energy compared to the two groups above them, and almost the same energy intake as the second most active group. Taken as a whole these two graphs support the contention that the obese develop appetite and energy dysfunction in response to poor quality diets, and this leads to a lack of physical activity and an increased consumption of energy.

Eat Well, Stay Healthy, Protect Yourself

RdB