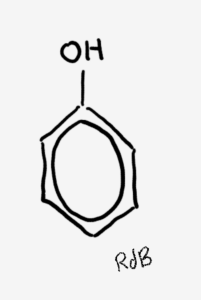

Plants are an important source of nutrients in human nutrition. As well as supplying the essential micronutrients and fibre, they also contain a range of chemicals that have been shown to be biologically active in humans. Some of these biologically active phytochemicals show possible protective effects against disease. Many of the phytochemicals in plants are polyphenolic, that is to say their structure is based around the presence of a phenol ring (figure 1). Phytochemicals that fall into this phenolic category include the flavonoids, stilbenes, terpenes, chalcones, isoflavones, sterols and alkylresorcinols. Epidemiological data suggests that polyphenols are associated with protection from certain diseases, most notably cardiovascular disease. Data from cell culture experiments shows antioxidant and gene regulatory effects for polyphenols. The biochemical effects of polyphenols in humans may include anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, antidiabetic, antiobesity, antiallergic and hepatoprotective effects.

Figure 1. The structure of a phenolic ring on which all polyphenols in plants are based. Polyphenols are secondary metabolites and over 8000 are known, although only a few hundred are nutritionally important to humans in edible plants.

Because of their health effects against chronic diseases, it is no surprise that consumption of polyphenols may be associated with improved longevity. For example, in a study published in the Journal of Nutrition1, researchers investigated the associations between total dietary polyphenols and total urinary polyphenols with mortality in 807 subjects aged 65 years or older from the Chianti region of Tuscany. The level of total urinary polyphenols was measured using a biochemical assay (the Folin-Ciocalteu method for gallic acid equivalents) and total dietary polyphenols were estimated from 4-day food diaries. Using the Kaplan-Meier survival model (here), the researchers then looked for associations between polyphenols and mortality. The results showed that total urinary polyphenols were higher in those subjects that survived longer, such that those with the highest total urinary polyphenol concentrations survived longer than those with the lowest. However, no significant effects were seen for total dietary polyphenols.

These results support previous studies in that they show protective effects for polyphenols against disease. The fact that total urinary polyphenols were associated with a reduced risk of mortality whereas total dietary polyphenols were not is interesting. This may represent discrepancies in the actual concentrations of polyphenols in foods compared to their estimated levels. Alternatively it may represent the fact that certain dietary polyphenols are not well absorbed or that genetic variation exists in the ability to absorb and excrete polyphenols from plant foods. Therefore while dietary intake might be higher in one individual compared to another, the actual amount of polyphenols that enter the circulation may be less. Using an actual biochemical measure of polyphenols in the urine may therefore more accurately reflect the levels of polyphenols in the circulation. The reason that polyphenols are associated with a reduced risk of mortality may relate to their anticancer and cardioprotective effects.

Dr Robert Barrington’s Nutritional Recommendation: plant polyphenols confer health benefits in humans. The best way to ensure that a protective effect is realised, is to eat a wide range of plant foods containing a wide range of different plant polyphenols. This is because the different polyphenols from various plants may have slightly different biochemical effects. In addition, a certain synergism is known to exist between different polyphenolic substances in terms of their cellular effects, and to take advantage of their synergism, a wide range of polyphenols must be consumed.

RdB